Georgia O’Keeffe, last chance!

[30 Nov 2021]The Pompidou Center’s major retrospective of Georgia O’Keeffe’s work will be ending on 6 December which means there are only a few days left to discover this immense American artist in Paris. Before the exhibition closes, Artprice takes a look at her career and some key market data.

The Pompidou Center exhibition opens with a space titled “Gallery 291”, the name of renowned photographer and gallerist Alfred STIEGLITZ’s Fifth Avenue gallery in New York where Georgia O’Keeffe’s artistic career really took off after many years as an art student, an art teacher and a commercial artist. In the early 20th century, Alfred Stieglitz showed work by the most avant-garde painters, sculptors and photographers of his era (Stieglitz was the first to show drawings by Rodin, Cézanne and Picasso on American soil). These were bold choices for the time, but they had little commercial impact because it was still too early. Mentalities and tastes were not yet fully acclimatized to Modern art. According to the legend, in 1916, charcoal drawings by the young O’Keeffe (originally from Wisconsin – and having previously studied art at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Art Students League of New York), were shown to Stieglitz who was the first to exhibit her drawings while she was still an art student at Teachers College Columbia University. There emerged a veritable artistic complicity between the two which soon developed into a long-standing close relationship. For years, the photographer supported the young painter by exhibiting her work regularly. Stieglitz thus fully contributed to Georgia O’Keeffe’s public recognition and gave her a place in a booming art market.

Modernity behind the flowers

Mirroring her strong personality and her work, Georgia O’KEEFFE (1887-1986) led an extraordinary life. In the 1920s, she began to paint urban landscapes and skyscrapers, considered male subjects. A choice so destabilizing at the time that Stieglitz himself initially refused to exhibit them, before accepting in 1925. The young woman went wherever her inspiration led her: from the buildings of Chicago and Manhattan to the grandiose landscapes of Lake George in upstate New York, via a very unique floral iconography. History has preferred to remember her floral paintings which have become her pictorial “signature”. Clearly the subject is more ‘gendered’, more feminine, than buildings, and so it was easier to categorize her under this theme. She is therefore primarily known for her paintings of giant flowers which she painted like no one else, magnifying them into monumental proportions, as gigantic as American cities and landscapes.

In 1923, an exhibition of her giant flower paintings excited the critics, who, according to Didier Ottinger, curator of the current exhibition at the Pompidou Center, detected “the expression of desire, female sexuality, even metaphors of the female orgasm”. Having recently discovered Freud’s theories, some art critics decided to see O’Keeffe’s paintings through a ‘psycho-sexual’ prism and were particularly inspired by the interpretations they attributed to her work, although the artist herself was less convinced. So although, in reality, the symbolism of sensual forms did not mean a great deal to her, the “sexualized” flowers ended up making her an essential artist on the American scene of her century.

Indeed, in 1929, the year the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) was inaugurated in New York (just a few days after Black Thursday), O’Keeffe was the first (and only) woman exhibited in the museum destined to be a great vehicle for European and American modernism. That same year, she discovered New Mexico, which would become her favorite place. From then on, she was divided between New York and a solitary life in a house bought in the middle of the desert looking out towards a superb mountain which became one of her great sources of inspiration.

In 1939, a jury was tasked with identifying the 12 most influential American women at the New York World’s Fair: O’Keeffe was one of them. Later, in 1943, she was the first woman to whom the Chicago Art Museum devoted a retrospective, followed by the MoMA in 1946, the year of Stieglitz’s death.

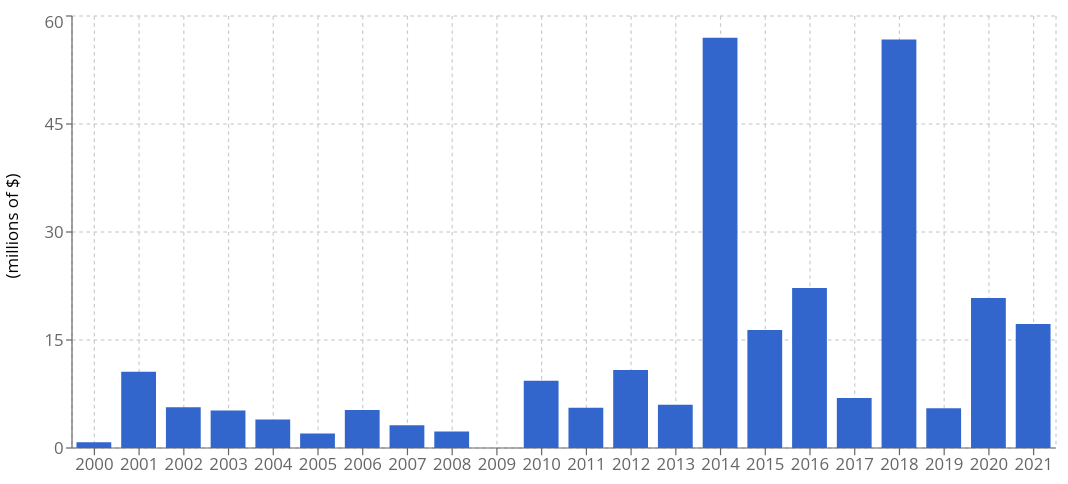

Chronological progression of O’Keeffe’s turnover at auction (copyright Artprice.com)

.

In 1968 she was pictured on the cover of Life magazine (“Stark visions of a pioneer painter”), and henceforward O’Keefe was definitively regarded as an American national icon, while being closely associated with New Mexico where she lived and painted for the last forty years of her life. Didier Ottinger reminds us that her career also coincided with “the emergence of an American feminism” which idolized her originality and independence considering that it had opened the way for the recognition of a ‘non-gendered’ art (except perhaps for the flowers…). This contributed to a certain ‘fetishization’ of her public persona which in turn attracted millions of visitors to the most recent major American exhibitions of her work (2017).

A pioneer of modernity, O’Keeffe was also a great source of inspiration for the new American artistic scenes of the second half of the 20th century. Her superb landscapes at the edge of figuration and abstraction paved the way for the great American abstract artists, including Mark Rothko.

First woman in the art market

Georgia O’Keeffe died in 1986. The Parisian exhibition is therefore a somewhat belated homage to her 35 years after her death. However, the international art market has been quicker to show its appreciation: in 2000, she was already ranked among the 30 top-selling performing artists in the world at auction by annual auction turnover. Her work has been firmly established as a staple of the American market for well over 20 years (her first 7-digit auction result dates back to 1987).

In 2014, Sotheby’s New York hammered an exceptional record of $44.4 million for one of her giant flowers (Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1. See image beside) making her the most expensive female artist in the world. This record has not been beaten since, but bidding for O’Keefe best works is definitely getting stronger. Last May, a smallish flowers painting (51 by 23 cm) sold for nearly $5 million, a record for such a small canvas. Her prices are rising for several reasons. First, because Georgia O’Keeffe is – as we have seen – an icon in American art history, and second because auction houses, major museums and certain collectors are consciously revalorizing the work of female artists. Lastly, her works in circulation are rare, as the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe (New Mexico) holds more than half of them. Fortunately, some lithographs (numbered) still offer the possibility of affordable acquisitions at around $10,000.

In 2014, Sotheby’s New York hammered an exceptional record of $44.4 million for one of her giant flowers (Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1. See image beside) making her the most expensive female artist in the world. This record has not been beaten since, but bidding for O’Keefe best works is definitely getting stronger. Last May, a smallish flowers painting (51 by 23 cm) sold for nearly $5 million, a record for such a small canvas. Her prices are rising for several reasons. First, because Georgia O’Keeffe is – as we have seen – an icon in American art history, and second because auction houses, major museums and certain collectors are consciously revalorizing the work of female artists. Lastly, her works in circulation are rare, as the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe (New Mexico) holds more than half of them. Fortunately, some lithographs (numbered) still offer the possibility of affordable acquisitions at around $10,000.

Key figures

167th – Georgia O’Keeffe’s current position in Artprice’s 2021 auction turnover ranking, thanks to seven lots sold for $5 million

$44.4 million – The record price for a female artist at auction, hammered at Sotheby’s New York on 20 November 2014 for her Jimson Weed / White Flower No. 1 (1932)

100% – The United States has accounted for all of Georgia O’Keeffe’s auction turnover since 2000. From France, bidding is easily done online or over the phone.

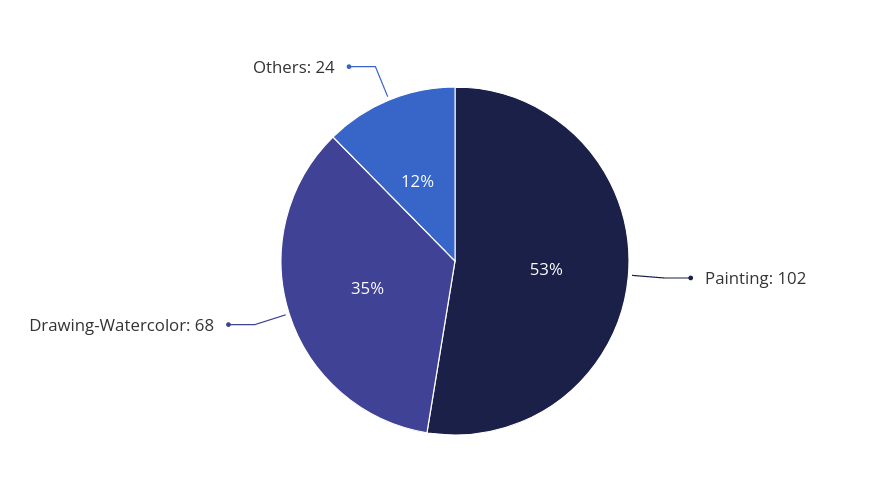

Georgia O’Keeffe: distribution by category (number of lots sold 2000-2021). Copyright Artprice.com

30.6

30.6